Questioning Techniques

- mrsstrickey

- Sep 22, 2020

- 9 min read

Why is questioning important?

Questions are the most common form of interaction between teacher and pupils in the whole-class lessons as well as in group and individual work.

Questioning is a key method of altering the level of challenge provided and determining the progress made in lessons.

It is the most immediate and accessible way of assessing learning.

What are the purposes of teachers' classroom questions?

A variety of purposes emerge from analysis of the literature, including:

To develop interest and motivate students to become actively involved in lessons

To evaluate students' preparation and check on homework

To develop critical thinking skills and inquiring attitudes

To review and summarize previous lessons

To nurture insights by exposing new relationships

To assess the achievement of instructional goals and objectives

To stimulate students to pursue knowledge on their own

Guidelines for Classroom Questioning

When teaching students factual material, keep up a brisk instructional pace, frequently posing lower cognitive questions.

With older and higher ability students, ask questions before (as well as after) material is read and studied.

Question younger and lower ability students only after material has been read and studied.

Ask a majority of lower cognitive questions when instructing younger and lower ability students. Structure these questions so that most of them will elicit correct responses.

Ask a majority of higher cognitive questions when instructing older and higher ability students.

Keep wait-time to about three seconds when conducting recitations involving a majority of lower cognitive questions.

Increase wait-time beyond three seconds when asking higher cognitive questions.

Questions to help pupils remember…

Recall questions are a teaching necessity. They’re a quick way of checking for misconceptions and they help to lock in key pieces of information. Using recall questioning strategies that involve all pupils can ensure pace and engagement and also help avoid a situation where only a few pupils (often the same ones) are involved. Here are a few ideas;

Mini whiteboards – pupils all show their answers at the same time.

Bingo – pupils select a number of keywords from the board and the teacher reads out definitions until someone gets a line or a full house.

What’s the question? – give pupils the answer and see how many questions they can come up with.

TV quiz shows – take your pick …Who wants to be a millionaire, Blockbusters etc. These work particularly well with an interactive whiteboard. Down the relevant music for extra impact.

Nomin8 – at the start of the lesson eight students are given a question each. The questions are typed and laminated leaving space for an answer – each student is given a non-permanent pen to record their ideas during the lesson. During the plenary, students present their answer. This also works well as a group activity.

Ask the panel – inform pupils that in groups of three or four they have four minutes to look through their books and identify what they think are the four main points so far in the topic they are doing at present. Ask the groups to convert the four main points they have identified into questions. Bring a group to the front to form a panel and the rest of the class then ask questions on the key points they have identified. Depending on the ability of the class you may wish to allow the panel to either confer, phone a friend (identify someone in the class for help) or have time out (look at their books for twenty seconds)

Killer – all students begin by standing up. One person is selected to start. You ask them a question, if they answer correctly they get to nominate the next person, if a question is incorrectly answered the player must sit down and the previous person who nominated them must nominate another pupil. Questions should be made up by the teacher on the spot; this will allow differentiation as required by the group.

The use of Edward de-Bono‟s Thinking Hats can be a useful resource for varying the type of question

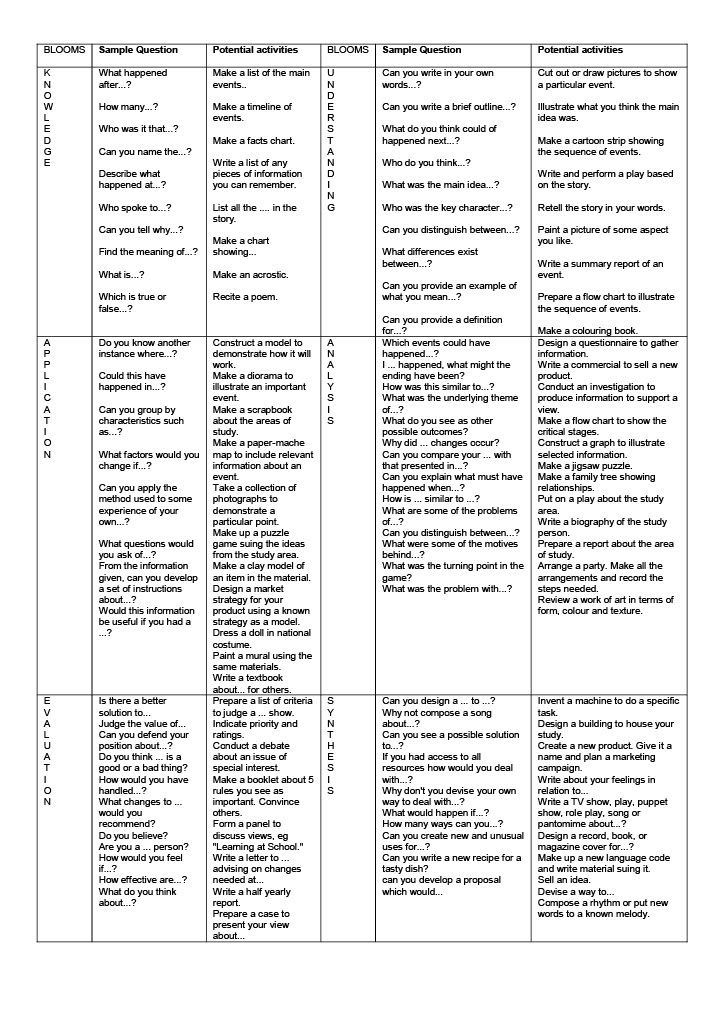

Bloom's Taxonomy

Bloom identified six levels of questioning, from the simple recall or recognition of facts, as the lowest level, through increasingly more complex and abstract mental levels, to the highest order which is classified as evaluation.

Examples of this are:

Evaluation: appraise, argue, assess, attach, choose compare, defend estimate, judge, predict, rate, core, select, support, value, evaluate.

Synthesis: arrange, assemble, collect, compose, construct, create, design, develop, formulate, manage, organize, plan, prepare, propose, set up, write.

Analysis: analyze, appraise, calculate, categorize, compare, contrast, criticize, differentiate, discriminate, distinguish, examine, experiment, question, test.

Application: apply, choose, demonstrate, dramatize, employ, illustrate, interpret, operate, practice, schedule, sketch, solve, use, write.

Understanding: classify, describe, discuss, explain, express, identify, indicate, locate, recognize, report, restate, review, select, translate,

Knowledge: arrange, define, duplicate, label, list, memorize, name, order, recognize, relate, recall, repeat, and reproduce state.

How to…. get everyone involved.

Introduce no hands up questioning. Give plenty of thinking time and make it safe by matching the question to the pupil carefully and by allowing them to pass. Above all, praise!

Move around the room. Ask someone to do a diagram of where you direct your questions – most of us are surprised by the results. By moving around the classroom, you are more likely to ask a wider range of pupils.

Give everyone a card at the beginning of the lesson and only take it back as a pupil answer a question. It’s easy to see at a glance which pupils haven’t answered a question.

Ask other pupils to add to an answer. E.g. ‘John, do you agree’, ‘Claire, what evidence can you find’ etc.

Once a pupil has answered a question, ask he or she to nominate another pupil to add some additional information or answer the next question – in the style of ‘phone-a-friend’.

Allow thinking time – you’ll be surprised at the difference it makes. The recommended wait time for a closed question is three seconds and for an open question, twenty seconds.

Allow discussion time – but keep it short and focused. Listen in on the discussion and plan specific questions for specific groups.

Allow planning time – preview the question and give pupils time to plan an answer. Use prompts where appropriate.

Vary your questioning strategies so that over a course of lessons pupils will experience different approaches.

Questions and thinking skills activities

Thinking skills activities are often stuctured around higher order questions and so can be an effective way of planning questions into a lesson.

Diamond ranking

This sorting activity can be used to encourage pupil discussion about the relative importance of individuals, incidents and ideas. Typically nine cards are given to a group of pupils (it can be more or less) and the cards are prioritised by placing the most important at the top, the least at the bottom and the others in the middle in a diamond formation. Questioning can be used to challenge and explore pupil thinking further.

Enquiry drama

This term covers a range of drama-based activities used to explore the emotions behind a character’s actions. Hot-seating a character and teacher in role are particularly useful – the Five Ws can be used as a questioning approach. In forum theatre, the action can be stopped so that pupils can direct or reflect on responses. Freeze frames can be used to identify critical moments and thought bubbles added to explore these further.

Five Ws

Who?

What?

Why?

Where?

When?

This approach to questioning can be linked to other activities such as reading photographs or used as an independent low maintenance thinking skills activity. It can also be a valuable display item that can be referred to in class discussion.

Fortune lines

This activity allows pupils to consider the impact of time on a particular person. Statements on small pieces of card are given to pupils along with a pre-printed chart showing a scale of positive to negative emotion. In groups, pupils place these cards on the chart - they must be prepared to justify their decisions. It is often interesting to show the fortunes of different characters on the same chart. Personalising a complicated piece of history in this way can make it more accessible to pupils. Living graphs are similar but they are based more on some form of hard data rather than on emotion.

Maps from memory

This is an excellent activity for getting pupils to look very closely at a particular image and also for getting them to develop collaborative skills. – planning, checking and group co-operation are all developed in deciding the best strategies for working. It often works well as an introduction to a unit. Working in groups of three or four, pupils take turn to visit the teachers desk to observe a diagram, map of picture for twenty seconds, with no pencil or paper for recording. They then go back to their group to draw and write what they can remember. After a short period of time, the next person goes up and the process is repeated, so that each pupil has, say, two goes. Finally, the original image is compared with the pupils’ versions. A starter activity could focus an useful strategies for this task and a plenary should certianly draw out the how as well as the what. Timing is very important in this activity so that pupil focus is not lost.

Mind and concept mapping

A mind map is a brainstorm of related ideas; a concept map shows the link between these ideas through some sort of labeling. This is a useful activity for establishing prior knowledge and revising knowledge and understanding. The format is particularly appealing to pupils with a preferred visual approach to learning. Mapping software is available (free and not!) and many teachers have found this invaluable in the classroom.

A Checklist for planning questions

Knowing as a basis for action

What basic knowledge does the learner need?

What particular skills does the learner need? (E.g. map-reading skills, ecology techniques, science skills, silk-screening procedures)

What are the relevant facts? And theories?

What skills does the learner need to find out for herself or himself? •

How is the work to be communicated? Does the learner have a variety of recording skills and techniques from which to choose?

Demonstrating understanding

Can the learner identify main points? Similarities? Differences?

Is it possible to ask any of these questions:

Can you explain in another way?

Why did this happen?

What were/will be the consequences?

How does this affect you/other people? Why?

Would you make the same decision? Why? Why not?

Looking for overall patterns and relationships

Can learners identify connections, sequences, patterns and themes?

Is it possible to ask any of these questions:

What is the overall plan?

How do the components fit together?

What is happening now?

What happened before?

What is likely to happen?

How do you feel about it?

Is it logical? Why? Why not?

Utilise the #bigquestionmatrix from Teacher Toolkit to help plan your questions in a lesson

And finally …. top ten tips!

Extend your wait time – at least three seconds for a closed question, longer for an open question.

Use ‘managing group talk’ strategies to allow pupils thinking/discussion time before sharing with the whole class.

Use follow up questions – Bloom’s Taxonomy can be useful here.

Withhold judgement!

Ask for a summary to promote active listening.

Survey the class – how many agree/disagree?

Play devil’s advocate – get pupils to do the same.

Encourage student questioning.

Stress that there is more than one answer.

Structure responses – time, number, post its!

Further Reading

QUESTIONING – TOP TEN STRATEGIES In The Confident Teacher by Alex Quigley10/11/2012

Academic Text

Alexander RJ (2006) Towards Dialogic teaching: rethinking classroom talk. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Dialogos.

Alexander RJ (2017) Towards Dialogic Teaching: rethinking classroom talk. 5th ed. Cambridge: Dialogos.

Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, Cruikshank KA, et al. (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Black P, Harrison C, Lee C, Marshall B and Wiliam D (2003) Assessment for Learning: Putting it into Practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Bloom BS (ed.) (1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Company, Inc.

Brooks, JG and Brooks MG (2001) Becoming a constructivist teacher. In: Costa: AL (ed.), Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking (pp.150–157). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Cavanaugh MP and Warwick C (2001) Questioning is an art. Language Arts Journal of Michigan 17 (2): 35–38.

Cohen L, Manion L, and Morrison K (2004) A Guide to Teaching Practice. London: Routledge.

Degener S and Berne J (2016) Complex questions promote complex thinking. The Reading Teacher 70 (5): 595–599. International Literacy Association.

Dekker-Groen A, Van der Schaaf M and Stokking K (2015) Teachers’ questions and responses during teacher-student feedback dialogues. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 59(2).

Hannel GI and Hannel L (2005) Highly effective questioning 4th ed. Phoenix AZ: Hannel Educational Consulting.

Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS and Masia BB (eds) (1964) Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: The affective domain. New York: McKay.

Lee Y and Kinzie MB (2012) Teacher question and student response with regard to cognition and language use. Instructional Science: An International Journal of the Learning Sciences 40(6): 857–874.

Morgan N and Saxton J (1991) Teaching Questioning and Learning. New York: Routledge.

Paramore J (2017) Questioning to stimulate dialogue. In: Paige R, Lambert S and Geeson R (eds) Building skills for Effective Primary Teaching. London: Learning Matters.

Samson GK, Strykowski B, Weinstein T and Walberg HJ (1987) The effects of teacher questioning levels on student achievement. The Journal of Educational Research 80(5): 290–295.

Tofade TS, Elsner JL and Haines ST (2013) Best practice strategies for effective use of questions as a teaching tool. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 77 (7) Article 155.

Wilen WW (1986) Questioning skills, for teachers. Washington DC: National Education Association.

Woolfolk A, Hughes M and Walkup V (2008) Psychology in Education. Harlow: Pearson.

Wragg EC (1993) Questioning in the Primary Classroom. London: Routledge.

Comments